Thomas Moore writes in his delightful book Original Self: “Memory holds us together as individuals and communities. When we forget who we have been, we lose a full sense of who we are.” (p.22)

Forgetting is akin to erasing memory, perhaps the only way we know to survive an overwhelming personal or historical event, but ultimately forgetting prevents us from feeling fully connected to the past. Each time we avoid something painful and turn away we cut something of ourselves away with it. In the state of reactive disconnection we move further and further from ourselves and increasingly feel more fragmented and lost.

One of our deepest instincts in overwhelming trauma is to dissociate from it in order to survive emotionally and deny the pain inside. This dissociated pain does not go away. It shows up in our reactive patterns, our triggers, our diagnoses, our dreams or nightmares, and our body symptoms. It also shows up in our culture as we collectively dissociate from historical and current situations we believe are unbearable to keep in mind. In my understanding this is why the Jewish community places so much importance on remembrance of the Nazi holocaust.

History is valuable. Without it we no longer realise who we are or where we have come from. We feel lost, astray, and unable to know ourselves. Meaning is lost, and with it that sense of purpose for life. When meaning is lost, despair appears.

Memory is a form of imagination. It is not literal recall, but a personalised recollection. Ask any detective and they’ll tell you each witness remembers the same scene or suspect differently. Ask your siblings and you’ll discover that beyond the literal facts you have in common they grew up in a different scenario than the one you remember. In my family, the grandmother who I loved deeply for her kindness and love, was experienced by my sister as an uncaring woman who disliked her. Where I felt safe with this grandmother my sister felt barely tolerated. It may be a challenge to accept all versions as true. Yet for personal healing and soul-making, it is the emotional or felt truth that is more relevant than the literal facts. This is the narrative thread, the meaning we make, and the relevance an event has for our ongoing lives.

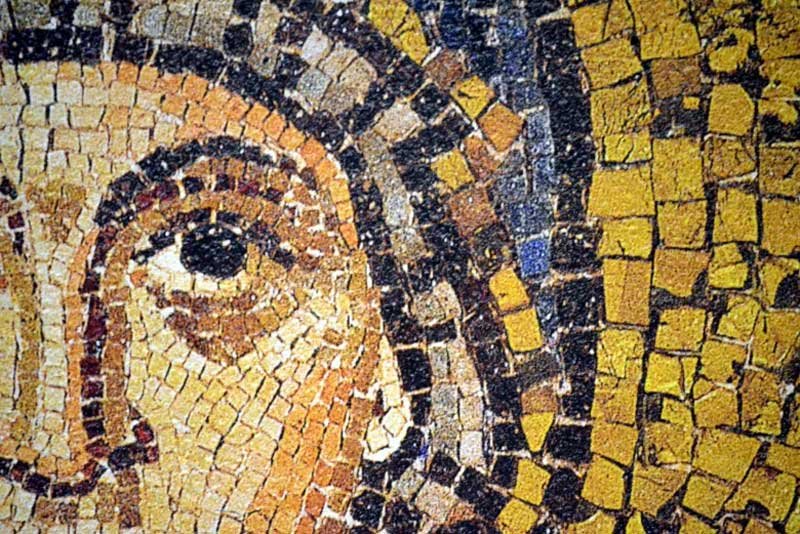

The powerful thing about memory is its imaginal dimension. While we want objective and verifiable truth when apprehending a suspect in order to ensure justice, in terms of the soul we thrive on the emotional and symbolic tone and meaning of our own memory. This is why good fiction can have a greater impact on us than an historically accurate biography. Imagination raises an event into the realm of story, metaphor and meaning. Memory and reverie, are arts that may reveal to us the personal and archetypal images that guide our life or that overlay our events.

The powerful thing about memory is its imaginal dimension. While we want objective and verifiable truth when apprehending a suspect in order to ensure justice, in terms of the soul we thrive on the emotional and symbolic tone and meaning of our own memory. This is why good fiction can have a greater impact on us than an historically accurate biography. Imagination raises an event into the realm of story, metaphor and meaning. Memory and reverie, are arts that may reveal to us the personal and archetypal images that guide our life or that overlay our events.

Trauma is in part traumatic because the survival mechanism disconnects memory and literalises our world and ourselves. We may lose any sense of story with breadth and depth, and ultimately our sense of humanness, either expecting ourselves to be perfect or living like automatons.

In therapy, or in a journal or some other frame or container that helps us gather and witness memories, we may begin to distil a deeper meaning beyond the question how could this happen to me? This memory-gathering enriches life, and cultivates meaning and purpose. This is different from the cold hard digging for trauma memories that actually re-traumatise and create more pain. There’s a delicate art here in being willing to gently engage with memories that return spontaneously but not try to dig up things not yet willing to sprout.

We do not need to wrench meaning from a memory. As Thomas Moore suggests: “… just remarking on it, mentioning it to a friend, even noting it to yourself, gives it the slightest honour. We might just recite the memory, however fragmentary, and not give in to the idle curiosity involved in trying to make sense of it.” (Original Self, p.21).

– With you on the journey, Violet

Recent Comments